The Kondratiev Wave is an important element of World-Systems Theory. The graphic above is taken from Andreas Goldschmidt and gives historical specifics for technological cycles. Goldschmidt's formulation allows for the idea to be tested (one of the models I always test), is consistent with economic Growth theory (particularly exogenous disembodied technological change in the Solow-Swan Model) and I present some examples below.

State Space Models

Wednesday, July 9, 2025

Technological Long Waves

The Kondratiev Wave is an important element of World-Systems Theory. The graphic above is taken from Andreas Goldschmidt and gives historical specifics for technological cycles. Goldschmidt's formulation allows for the idea to be tested (one of the models I always test), is consistent with economic Growth theory (particularly exogenous disembodied technological change in the Solow-Swan Model) and I present some examples below.

Tuesday, July 8, 2025

The Iranian Revolution

Notes

Further reading:

Iranian Revolution a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1979.

Strait of Hormuz a strait between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. It provides the only sea passage from the Persian Gulf to the open ocean and is one of the world's most strategically important choke points.

Iran-Contra Affair a political scandal in the United States that centered on arms trafficking to Iran between 1981 and 1986, facilitated by senior officials of the Ronald Reagan administration

Iran Nuclear Program one of the most scrutinized nuclear programs in the world, has sparked intense international concern.

Pahlavi Iran the Iranian state under the rule of the Pahlavi dynasty. The Pahlavi dynasty was created in 1925 and lasted until 1979 when it was ousted as part of the Iranian Revolution, which ended the Iranian monarchy and established the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Iran-Iraq War an armed conflict between Iran and Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. Active hostilities began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for nearly eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations Security Council Resolution 598 by both sides.

Iranian Economy a mixed, centrally planned economy with a large public sector. It consists of hydrocarbon, agricultural and service sectors, in addition to manufacturing and financial services, with over 40 industries traded on the Tehran Stock Exchange.

The White Revolution a far-reaching series of reforms to aggressively modernize the Imperial State of Iran launched on 26 January 1963 by the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and ended with his overthrow in 1979.

Modernization Theory holds that as societies become more economically modernized, wealthier and more educated, their political institutions become increasingly liberal democratic and rationalist.

Foreign Policy of the Kennedy Administration The United States foreign policy during the presidency of John F. Kennedy from 1961 to 1963 included diplomatic and military initiatives in Western Europe, Southeast Asia, and Latin America, all conducted amid considerable Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union and its satellite states in Eastern Europe.

Blog Roll:

- Stabilizing the Iranian Economy Easy but not easy!

- A Deep Dive into the Iranian State Space Cycles vs. Control.

- The Iranian Revolution Still being worked out today.

- Will Israel and US Attacks Hurt the World-System? Yes

- How Does the Iranian Economy Work? Not like a Neoclassical, free-market economy.

- What was the Impact of the Iranian Revolution? Elimination of Cycles!

- Iranian Globalization and Unemployment Created the discontent that led to the Iranian Revolution.

Friday, June 27, 2025

World-System (1950-2190) Stabilizing the Iranian Economy

The graphic above shows a forecast for Iranian growth that reaches a steady state sometime after 2190. It involves a simple change to the IR_LM model. The growth parameter is simply changed from 1.01282761 to 0.98, a reduction of about 0.03%--slowing growth not economic stagnation.

Getting countries to reduce growth rates is not simple matter, as the IPCC has found when trying to control climate change. But, it is the same lesson demonstrated by the Limits to Growth models and System Theoretic considerations.

For Iran, Instability (unstable Systemic Growth) was created by the pressure to Modernize, both from the Pahlavi dynasty and from the Foreign Policy of the Kennedy Administration (Walt Rostow, one of Kennedy's Academic Brain Trust, was a strong advocate of "take-off into sustained growth" (the definition of historical instability in the Growth Component IR1) and a fundamental tenant of Modernization Theory

Notes

Further reading:

Iranian Revolution a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1979.

Strait of Hormuz a strait between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. It provides the only sea passage from the Persian Gulf to the open ocean and is one of the world's most strategically important choke points.

Iran-Contra Affair a political scandal in the United States that centered on arms trafficking to Iran between 1981 and 1986, facilitated by senior officials of the Ronald Reagan administration

Iran Nuclear Program one of the most scrutinized nuclear programs in the world, has sparked intense international concern.

Pahlavi Iran the Iranian state under the rule of the Pahlavi dynasty. The Pahlavi dynasty was created in 1925 and lasted until 1979 when it was ousted as part of the Iranian Revolution, which ended the Iranian monarchy and established the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Iran-Iraq War an armed conflict between Iran and Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. Active hostilities began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for nearly eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations Security Council Resolution 598 by both sides.

Iranian Economy a mixed, centrally planned economy with a large public sector. It consists of hydrocarbon, agricultural and service sectors, in addition to manufacturing and financial services, with over 40 industries traded on the Tehran Stock Exchange.

The White Revolution a far-reaching series of reforms to aggressively modernize the Imperial State of Iran launched on 26 January 1963 by the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and ended with his overthrow in 1979.

Modernization Theory holds that as societies become more economically modernized, wealthier and more educated, their political institutions become increasingly liberal democratic and rationalist.

Foreign Policy of the Kennedy Administration The United States foreign policy during the presidency of John F. Kennedy from 1961 to 1963 included diplomatic and military initiatives in Western Europe, Southeast Asia, and Latin America, all conducted amid considerable Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union and its satellite states in Eastern Europe.

Blog Roll:

- Stabilizing the Iranian Economy Easy but not easy!

- A Deep Dive into the Iranian State Space Cycles vs. Control

- The Iranian Revolution Still being worked out today.

- Will Israel and US Attacks Hurt the World-System? Yes

- How Does the Iranian Economy Work? Not like a Neoclassical, free-market economy.

- What was the Impact of the Iranian Revolution? Elimination of Cycles!

- Iranian Globalization and Unemployment Created the discontent that led to the Iranian Revolution.

Tuesday, April 22, 2025

World-System (1450-1540) France, Spain or Go It Alone for England

Thursday, April 17, 2025

World-System (1450-1650): Anne of Cleves and the German Connection

In the graphic above, I have presented alternative growth forecasts for Germany (1450-1640). The dark line is the actual data path and the remaining lines are for the Random Walk (RW), the Business as Usual (BAU) and the World System linkages (W). All the forecasts are similar. After 1600, the Germany was heading for a steady state economy. As I have shown earlier, England would have better going it alone (BAU) or following the World System (here). In any event, alliance with Germany was a path not taken because Henry's marriage to Anne of Cleves quickly failed. Anne was smart enough to take a generous settlement from Henry and she managed to outlive both Henry and Cromwell.

You can explore alternative economic histories for Germany using the DE_L16 model (here) and consult the Boiler Plate (here) for more information about how the state space models were constructed. You can also read my discussion of the German Economy during this period here. And, you can imagine that, rather than Anne of Cleves looks being a factor, John Dee had gotten to Henry with the German growth forecast and convinced him that an alliance was not such a good idea.

Thursday, April 3, 2025

World-System 1540: John Dee makes a Growth Forecast for England

In a prior post (here), John Dee had given Henry VIII a forecast for World System growth. The forecast was not well received. "Who canst fathom a World System?" Henry mumbled as Master Thomas Cromwell led Dee out of the King's chambers, from where Dee returned to his library to divine his next steps.

Henry had asked for something more specific, a forecast for England for example. Dee twirled his protractor, consulted the Angels and came up with the forecasts in the graphic above, unaccountably plagiarized from both my WL16 model and my UKL16 Model. Dee appropriated the original UK1 data (dark line above) and three forecasts: the Random Walk (RW, history is just one damned thing after another), the Business as Usual (BAU) model and a model using the World System state variables (W) as inputs.

Dee was a little nervous about the forecasts, so he presented them first to Cromwell. Cromwell was shocked; there was the World System forecast again (the one Henry did not understand) and now Dee had shown it to be far superior to the more reasonable BAU (England goes it alone) forecast. And having looked into the Future, Dee concluded that England would pursue the BAU path at least to the 1600s (if not to the present and here).

"Dr. Dee, you will have to present the forecast yourself to the King. I needst not be asked to render my opinion." History did not record the meeting between Henry VIII and Dr. Dee but Dee did not lose his head (Cromwell thought "...he will have his head loosed from his shoulders...") and managed to outlive both Henry and Cromwell (John Dee died in poverty and obscurity either in 1608 or 1609). History has recorded Dee's attempts to consult the Angels and explain Henry's failed marriages in terms of Geopolitical divinations. I will report those analyses in future posts.

Season 2, Episode 3 of Wolf Hall premiers this Sunday (April 6, 2025) and it begins Thomas Cromwell's fall from power. Not to be missed! You can stream Season2, Episode 3, Defiance or watch it over the air on Sunday.

Notes

Monday, March 31, 2025

What is a System?

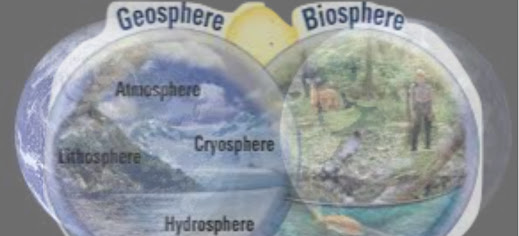

In the past, I was not one who cared much for definitions. Now, I realize that the lack of clear definitions, particularly in the Social Sciences, has led to unnecessary misunderstanding. For example, in grade school, students learn that the Earth is a complex system with a number of spheres and feedback loops (see the graphic above--humans are located in the Biosphere). Then, students get to college and (might) learn in a Sociology course that there is (or maybe there isn't) a Capitalist World System. Or, they might read that the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) is having trouble identifying feedback loops in Human Systems. Then they might go back to Sociology (or Economics) and find that feedback loops are never discussed and that even the concept of a system is not taken very seriously.

Just to make the discussion somewhat more concrete, does the graphic above (the Kaya Identity used by the IPCC) describe a system (where N=Population, Q=Output, E=Energy, CO2=Carbon Emissions and T = Global Temperature)? The extensive variables (N, Q, E, CO2 and T) are causally connected. The Impact (I=PAT) is described by the intensive variables (q=Q/N, e=E/Q, c=CO2/E and t=T/CO2).